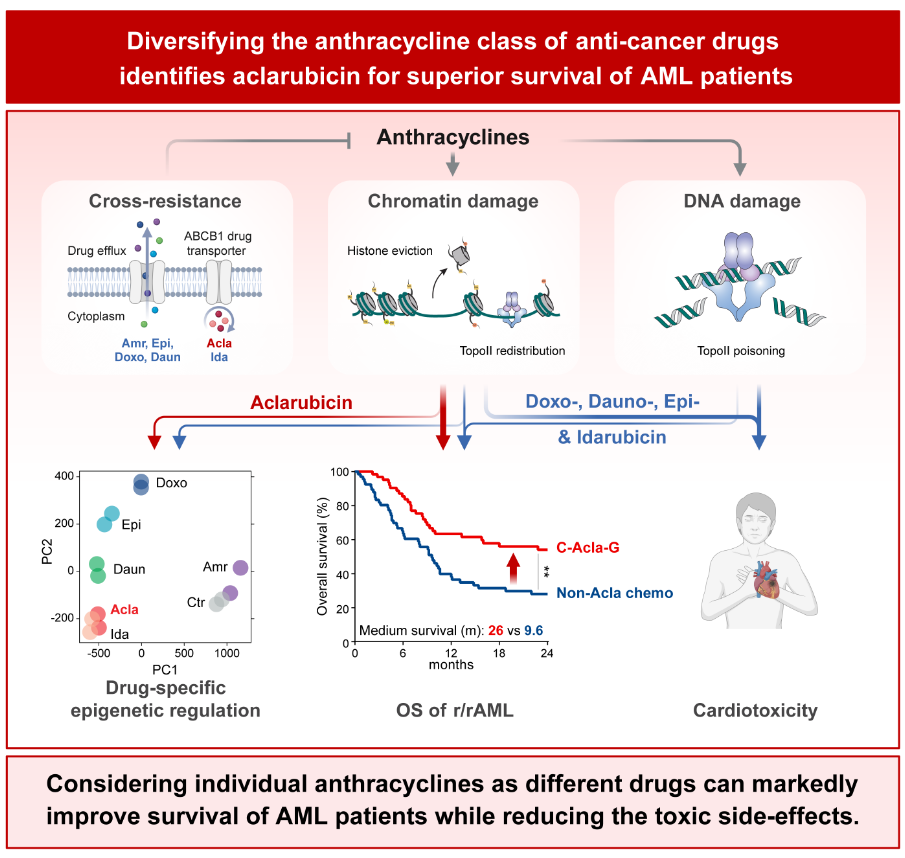

Aclarubicin is a member of the anthracyclines group. Antracyclines are a group of drugs given as chemotherapy for various cancers. This form of chemotherapy treatment is highly effective but also increases the risk of heart damage. Patients should therefore be treated with anthracyclines only on a limited basis, and if the cancer returns, anthracycline-based treatments are no longer an option.

The search for the working mechanism of a “non-toxic” anthracycline called aclarubicin started with the 12-year-old Jeroen Krabbenbos, a boy with relapsed/refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). His family was looking for a last resort and approached Neefjes. Neefjes: “Aclarubicin was an option but was taken off the European market in 2004 because 'it didn't sell well enough.' Aclarubicin is still used in China and Japan for the treatment of AML, but it has been unclear to what extent heart failure would occur in these patients.

Researcher Xiaohang Qiao from the Netherlands Cancer Institute studied various anthracyclines both in the lab and in mice. Qiao: “We focused on how these drugs eliminate cancer cells and their associated side effects. Our studies revealed that aclarubicin can be safely administrated in mice and was well-tolerated, even after prior exposure to cardiotoxic anthracycline treatment.”

The researchers and the treating physician therefore contacted dr. Li in Shanghai. Dr. Li treats AML patients with aclarubicin. Thanks to the collaboration with Shanghai, the Neefjes lab gained access to data from patients who had been treated intensively with anthracyclines. The effects of different anthracyclines (including aclarubicin) could thus be compared. The main question was whether aclarubicin is an effective chemotherapy treatment that still can be used in patients with refractory AML, like the 12-year-old Koen.

“Based on the data from Shanghai, it appears that about 70% of patients with relapsed/refractory AML responded to aclarubicin-based therapy, and about 30% even recovered. In the Netherlands, the 5-year survival for AML patients is currently 30%. The results of this study show that the survival rate increases to 53% if patients with relapsed/refractory AML are treated with aclarubicin! “Lack of cardiac toxicity is the main reason for the success of aclarubicin because you can continue treatment,” Neefjes said. Patient data from Shanghai also shows that aclarubicin is more effective than venetoclax, the newest (and expensive) drug for AML. And that, unlike venetoclax, patients do not become desensitized when treated with the much cheaper aclarubicin.

Unfortunately, aclarubicin is currently not available to Dutch patients, and much work is needed to get the drug back on the European market. “Koen passed away shortly after the family contacted us. But thanks to his story, the collaboration with dr. Li came about and we have made great progress in researching the efficacy and safety of using aclarubicin in patients with relapsed/refractory AML.”

Because aclarubicin is not yet available for clinical trials in the Netherlands, clinical trials with dr. Li in China will be initiated to further investigate the use of aclarubicin against AML and other blood cancers. “We are working hard, so that our research can offer a perspective to AML and other blood cancer patients, for whom no treatment options are currently available,” Neefjes said.

Koen’s story is shared with the permission of his parents, in loving memory of their son.